Chapter 12 Applications of Differentiation

12.1 Maxima and Minima

“…nothing at all takes place in the universe in which some rule of maximum or minimum does not appear…”

Leonhard Euler

We quite often need to find maximum and minimum points of a function in relation to optimisation or due to some physical principle, such as the minimisation of potential energy in physics.

We distinguish between local maxima/minima and global maxima/minima. A global maximum is a “peak” in the graph of a function that is higher than or equal to any other value of the function, whilst a local maximum is a “peak” that is higher than or equal to any other value in the immediate region around the peak; we have similar definitions for a global and local minimum. If we are looking at maxima/minima where there are no points (globally/locally) that are equal in value, we add the word strict maximum/minimum. Differentiation can help us to find local maxima/minima.

We first mention some basic relationships between functions and their derivatives. These are all intuitively obvious (their mathematical proofs follow from the Mean Value Theorem).

Fermat’s Theorem. If \(x=a\) is a local maximum or local minimum point for \(f(x)\), then \(f'(a)=0\). The converse to this theorem is not true, e.g. for \(f(x)=x^3\), we have \(f'(0)=0\), but \(a=0\) is clearly not a local maximum or minimum for \(f\). We use the term critical point or stationary point for a point \(a\) at which the derivative \(f'(a)=0\).

Constant Function. If \(f'(x)=0\) for all \(x\) then \(f\) is constant (that is, \(f(x)=c\) for some constant \(c\)).

Constant Difference. If \(f\) and \(g\) are such that \(f'(x)=g'(x)\) for all \(x\), then there is some constant \(c\) such that \(f=g+c\) (geometrically this says that \(f\) is a vertical translation of \(g\)).

Functions with Positive or Negative Derivatives. If \(f'(x)>0\) for all \(x\), then \(f\) is strictly increasing. If \(f'(x)<0\) for all \(x\), then \(f\) is strictly decreasing. The converse is not true: consider again \(f(x)=x^3\) which is strictly increasing but has \(f'(0)=0\).

Note that in order to have a local maximum or minimum at a point \(x=a\) it is a requirement that \(f'(a)=0\), but this is not a sufficient condition to gaurantee we have a maximum or minimum at \(a\). We can determine if a critical point is a local maximum or minimum using the so-called second derivative test.

Theorem 12.1 (Second Derivative Test for Maxima and Minima) Suppose \(f'(a)=0\) (i.e. \(a\) is a critical point of \(f\)).

If \(f''(a)>0\), then \(f\) has a strict local minimum at \(a\),

If \(f''(a)<0\), then \(f\) has a strict local maximum at \(a\).

To understand this theorem, note that if \(f''(a)>0\) then this says that \(f'(x)\) is strictly increasing near \(a\) and we also know that \(f'(x)\) passes through \(0\) at \(x=a\). This means \(f'(a-\delta)<0\) and \(f'(a+\delta)>0\) for an arbitrary small number \(\delta>0\); that is, we have a negative gradient to the left of \(a\) and a positive gradient to the right of \(a\), hence \(a\) must be a local minimum of the function. A similar argument holds for \(f''(a)<0\) and \(a\) being a local maximum.

Warning! The function \(g(x)=x^4\) has a strict global (and hence also local) minimum at \(0\), where \(g'(0)=0\) but we have \(g''(0)=0\), hence the converse to the Second Derivative Test is not true.

12.2 Points of Inflection

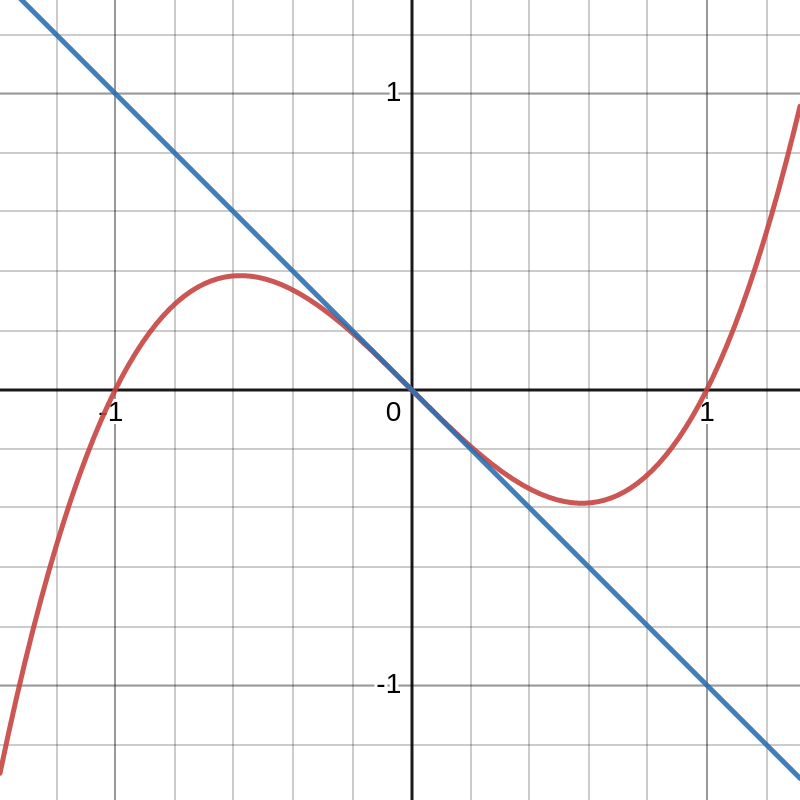

An inflection point \(x=a\) is a point where the tangent line to a graph of a function \(f\) at \((a,f(a))\) crosses the graph at \((a,f(a))\). This corresponds to a point where the graph changes from being convex to concave (or vice versa).

Figure 12.1: Inflection points

It is necessary that the second derivative has different signs to the left and right of \(a\) for it to be an inflection point, and hence \(f''(a)=0\). But note that \(f''(a)=0\) alone is not sufficient for \(a\) to be an inflection point (for example, \(f(x)=x^4\) at \(x=0\) has derivative \(f''(0)=0\), but this is a minimum). Note that we do not need \(f'(a)=0\), so a point of inflection is not necessarily a critical point. Having a nonzero third order derivative at a point \(a\) where \(f''(a)=0\) ensures that the second derivative has different signs to the left and right of \(a\).

Theorem 12.2 (Third Derivative Test for Inflection Points) If \(f''(a)=0\) and \(f'''(a)\neq 0\) then \(a\) is a point of inflection

Warning! The function \(g(x)=x^5\) has a point of inflection at \(0\), but with \(g''(0)=0\) and \(g'''(0)=0\). This demonstrates that the above criteria on the third derivative is sufficient but not necessary.

12.3 Higher Order Derivative Test

We can generalise the above derivative tests to determine whether critical points are maxima, minima or inflection points based on higher order derivatives.

Theorem 12.3 (Higher Order Derivative Test) Let \(f\) be a sufficiently differentiable function on an interval containing the point \(a\). If with \(n>1\) we have \(f^{(i)}(a)=0\) for \(i=1,\dotsc,{n-1}\) but \(f^{(n)}\neq 0\), then

- If \(n\) is even and \(f^{(n)}<0\), then \(a\) is a strict local maximum point

- If \(n\) is even and \(f^{(n)}>0\), then \(a\) is a strict local minimum point

- If \(n\) is odd and \(f^{(n)}<0\), then \(a\) is a strictly decreasing point and an inflection point

- If \(n\) is odd and \(f^{(n)}>0\), then \(a\) is a strictly decreasing point and an inflection point

Note that the test can fail if the higher order derivatives at \(a\) cease to exist before they become non-zero, or if the derivatives of \(f\) at \(a\) of all orders are zero i.e. \(f^{(i)}(a)=0\) for all \(i\).

12.4 Graph Sketching

We now have a lot of tools to help us understand the nature of a function and to sketch graphs. We can analyse a function \(f\) by looking at:

- the values \(x\) where \(f(x)=0\), i.e. where the graph crosses the \(x\)-axis

- the value of \(f(0)\), i.e. where the graph crosses the \(y\)-axis

- the critical points of \(f\) (possibly local maxima/minima, inflection points) and the value of \(f\) at these critical points

- the sign of \(f'\)

- the location and nature of any vertical asymptotes

- if the function is periodic

12.5 Optimisation

Optimisation is the process of finding the “best” inputs, that maximise or minimise some objective function. For suitable objective functions we can use our derivative tests to find these inputs.

Here we shall look at an example and give a general method for solving such problems.

Example 12.1 (A fencing problem) A rectangular storage compound needs to be built on a building site. An existing wall is to be used as one side of the compound and the other 3 walls will be built with fencing. There is 100m of fencing available. What is the maximum storage area that can be built and what are the lengths of the sides?

Let the side opposite the wall have length \(y\) and the other two sides length \(x\). The length of the fencing will be the perimeter of these three sides, hence

\[2x+y=100 m\]

We want to maximise the area, hence our objective function is

\[A=x\times y.\]

We use the first equation to find \(y\) in terms of \(x\):

\[y=100-2x\]

then

\[A=x(100-2x)=100x-2x^2.\]

To maximise, we need to find the solution for \(\frac{dA}{dx}=0\):

\[\frac{dA}{dx}=100-4x=0\quad\implies\quad x=25 m\]

We check this is a maximum at \(x=25\). We have

\[\frac{d^2A}{dx^2}=-4\]

which is indeed negative, hence we have a maximum at \(x=25\). Substituting back into our equations for \(y\) and \(A\) we have: \[\begin{align*} x&=25m\\ y&=50m\\ A&=1250 m^2. \end{align*}\]

Methodology

- Obtain an expression for the quantity that must be maximised or minimised;

- Ensure that the expression is in terms of just one unknown variable;

- Get the resulting expression into a form that can be differentiated;

- Differentiate the function and set equal to zero;

- Solve for the unknown variable, i.e. find the critical points;

- Find the second derivative of the function and check which critical points are maxima/minima;

- Substite the points back into the objective function (in terms of the one variable) to find the values at these points – select the largest/smallest.